At Asiahop, we’ve prepared this introduction to ramen (ラーメン) so you can learn the essentials before traveling to Japan and enjoy your culinary experiences to the fullest. Here, you’ll find a visual tour of the best types of ramen in Japan, accompanied by photographs.

We also share the fascinating history of ramen, its traditional ingredients, and the Japanese regions with the most popular varieties of this iconic dish. With this article, you’ll learn to appreciate ramen in all its complexity, recognize its components, and discover the rich culture that has developed around this culinary delight for over a century.

In this article about ramen, you’ll find:

- Ramen ingredients and what types are there

- Ramen toppings

- Famous types of ramen

- Delicious, lesser-known ramen

More Than Just a Noodle Soup

When we think about Japanese cuisine, ramen has become one of its most recognized ambassadors worldwide. However, behind this seemingly simple bowl of noodles and broth lies a rich history, refined techniques, and surprising diversity.

Ramen has its roots in Chinese cuisine, arriving in Japan at the end of the 19th century when the country was beginning to open up to the world after centuries of isolation. An important milestone was the opening of the Rairaiken restaurant in 1910 in the Asakusa neighborhood of Tokyo, considered the first documented ramen establishment in Japan. In these early years, Chinese “lamian” (拉麺) noodles were gradually adapted to Japanese tastes, transforming into what we know today as ramen.

The etymology of the word “ramen” reflects this evolution: initially known as “shina soba” (支那そば) or “chuka soba” (中華そば), both terms meaning “Chinese noodles,” the dish was renamed over time. The current term “ramen” derives from the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese term “lamian,” which literally means “stretched noodles.”

It was during the Showa period (1926-1989), and especially after World War II, that ramen experienced its greatest boom in Japan. Rice shortages led to a search for food alternatives, and wheat imported primarily from the United States allowed the noodles to become popular. For Japanese people facing difficult times, a hot bowl of ramen represented not only an affordable luxury but a symbol of the country’s economic recovery.

Over time, ramen went from being a foreign dish to becoming an emblem of Japanese culinary adaptability. Each region began to develop its own style, incorporating local ingredients and unique techniques, thus creating a hybrid culinary identity that is profoundly Japanese in its philosophy, yet Chinese in its origins. This transformation perfectly embodies the Japanese concept of “wakon yosai” (和魂洋才) – Japanese spirit, Western knowledge – applied to gastronomy.

The Four Pillars of Ramen

Ramen is not simply a noodle soup; it is a meticulous balance of four fundamental elements that, when combined, create a symphony of flavors and textures.

The Broth (スープ, sūpu)

The soul of ramen is undoubtedly its broth. Preparing a good broth can take from several hours to days of slow cooking, extracting deep flavors from bones, meats, seafood, and vegetables. In more traditional restaurants, broths can cook for over 12 hours, maintaining precise temperature control to extract maximum flavor without developing bitterness.

Ramen masters distinguish between two main categories of broth:

- Chintan (清湯): Clear, transparent broths, prepared over medium-low heat to avoid clouding the liquid.

- Paitan (白湯): Cloudy, creamy broths, prepared over high heat with constant stirring to emulsify fats and collagens.

There are four main styles of broth:

- Tonkotsu (豚骨): Originating in Kyushu, it is made by boiling pork bones for hours over high heat until a creamy, cloudy, and extremely rich paitan-style broth is achieved. Its whitish color and creamy texture are unmistakable. The ideal cooking temperature is between 96-98°C to maximize collagen extraction without overly clouding the broth.

- Shio (塩, “salt”): This is the lightest and clearest style, typically a chintan-style ramen. It is based on a chicken broth and sometimes seafood such as niboshi (煮干し), small dried anchovies, katsuobushi (鰹節), which are dried bonito flakes, and kombu seaweed (昆布), seasoned primarily with salt. It is clear and refreshing, allowing subtleties of flavor to be appreciated.

- Shoyu (醤油, “soy sauce”): A chicken and vegetable-based broth, seasoned with soy sauce, which gives it a characteristic amber color. It is balanced, with a well-defined umami profile, and represents the classic Tokyo style. High-end ramen restaurants often create their own custom shoyu blends, often in collaboration with traditional soy sauce makers.

Miso (味噌): The most recent of the four varieties, originating in Hokkaido in the 1950s. It uses fermented miso paste to create a robust and comforting broth, ideal for the harsh winters of northern Japan. Variations exist that combine different types of miso (red, white, yellow) to achieve a unique flavor profile.

Furthermore, contemporary chefs are exploring alternative bases such as vegetarian broths enhanced with mushrooms and ferments, or poultry broths such as duck or pheasant to create gourmet experiences.

Noodles (麺, men)

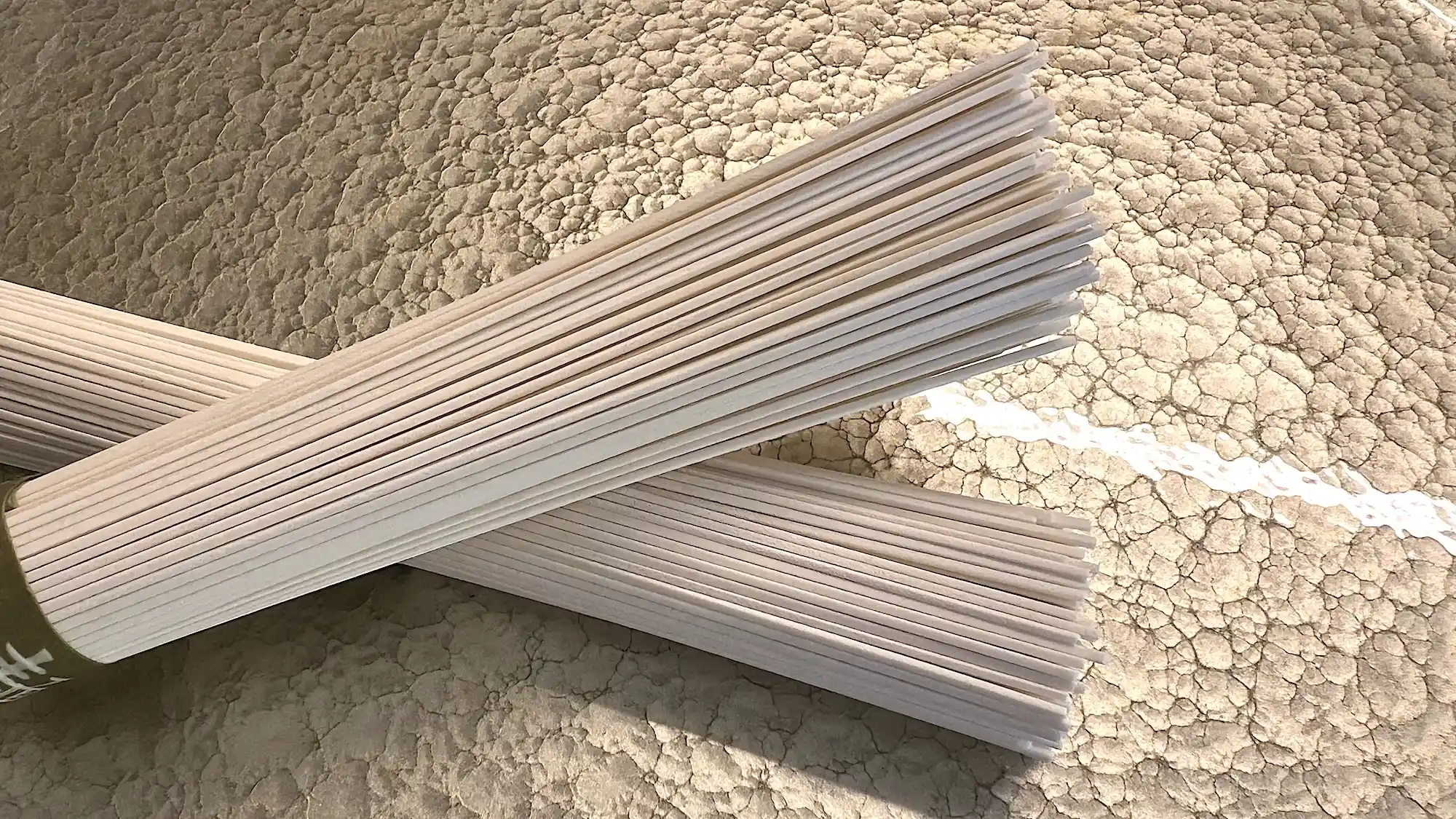

The second star ingredient in ramen is the noodles. Their texture, thickness, and shape vary depending on the style of ramen. Made with wheat flour, water, salt, and kansui (水, an alkaline solution that gives them their characteristic yellowish color and elasticity), ramen noodles are a science in themselves.

The traditional production process begins with kneading, followed by a resting period for the dough that can vary from 1 to 24 hours depending on the recipe. This resting period allows the gluten to develop properly, giving the noodles their characteristic elastic texture. The hydration percentage varies significantly: from 32% for very firm noodles to 40% for softer varieties.

The noodles are cut into different thicknesses using specialized machines, some of which are decades-old relics, whose worn rollers give the noodles a unique character. Master craftsmen can distinguish thickness variations of tenths of a millimeter.

Thin, straight noodles (細麺) called “hosomen” are often paired with thin broths like shio or shoyu, allowing for quicker absorption of flavor. On the other hand, thick, wavy noodles (太麺) called “futomen” are often paired with richer broths like tonkotsu or miso, as their texture and shape better retain these thick broths.

At the best ramen-ya (拉麵屋), as ramen restaurants are called, noodles are cooked with millimetric precision to achieve that perfect consistency. Customers can specify their desired consistency using terms like “katame” (固め, firm), “futsuu” (普通, regular), or “yawarakame” (柔らかめ, soft). The optimal cooking time is usually between 40 seconds and 2 minutes, depending on the thickness.

Tare (タレ)

Tare is a concentrated flavor and is probably the least visible component of the dish but most defining of the character of a good ramen. Tare is a concentrated sauce placed at the bottom of the bowl before pouring the broth, and it determines whether we are dealing with shoyu, shio, miso, or any other variant of the ramen. It gives it depth of flavor and distinction.

Ramen masters closely guard their tare recipes, which often include secret combinations of aged soy sauce, mirin (味醂, sweet rice wine), sake, spices, dried mushrooms, and other umami enhancers. Some historic establishments use tare bases that have been constantly evolving for decades, something known as “tane-dare” (種タレ) or “seed tare,” to which new ingredients are periodically added while maintaining a portion of the original.

The ratio of tare to broth is crucial: it generally ranges between 1:10 and 1:13, depending on the desired intensity. A mistake in this ratio can ruin the balance of the entire dish.

Regional and specialty variations include:

- Yuzu-shio tare: With yuzu citrus for a refreshing flavor.

- Kara-miso: Spicy miso tare with toban-jan (spicy bean paste).

- Mayu: Charred black garlic oil that adds smoky depth.

This component is so defining that two ramen dishes can use the exact same broth but be completely different due to the tare used.

Ramen Toppings (トッピング, toppingu)

The final touch to the dish is provided by the selection of toppings, carefully chosen to harmonize with the rest of the ramen ingredients. Among the most common are:

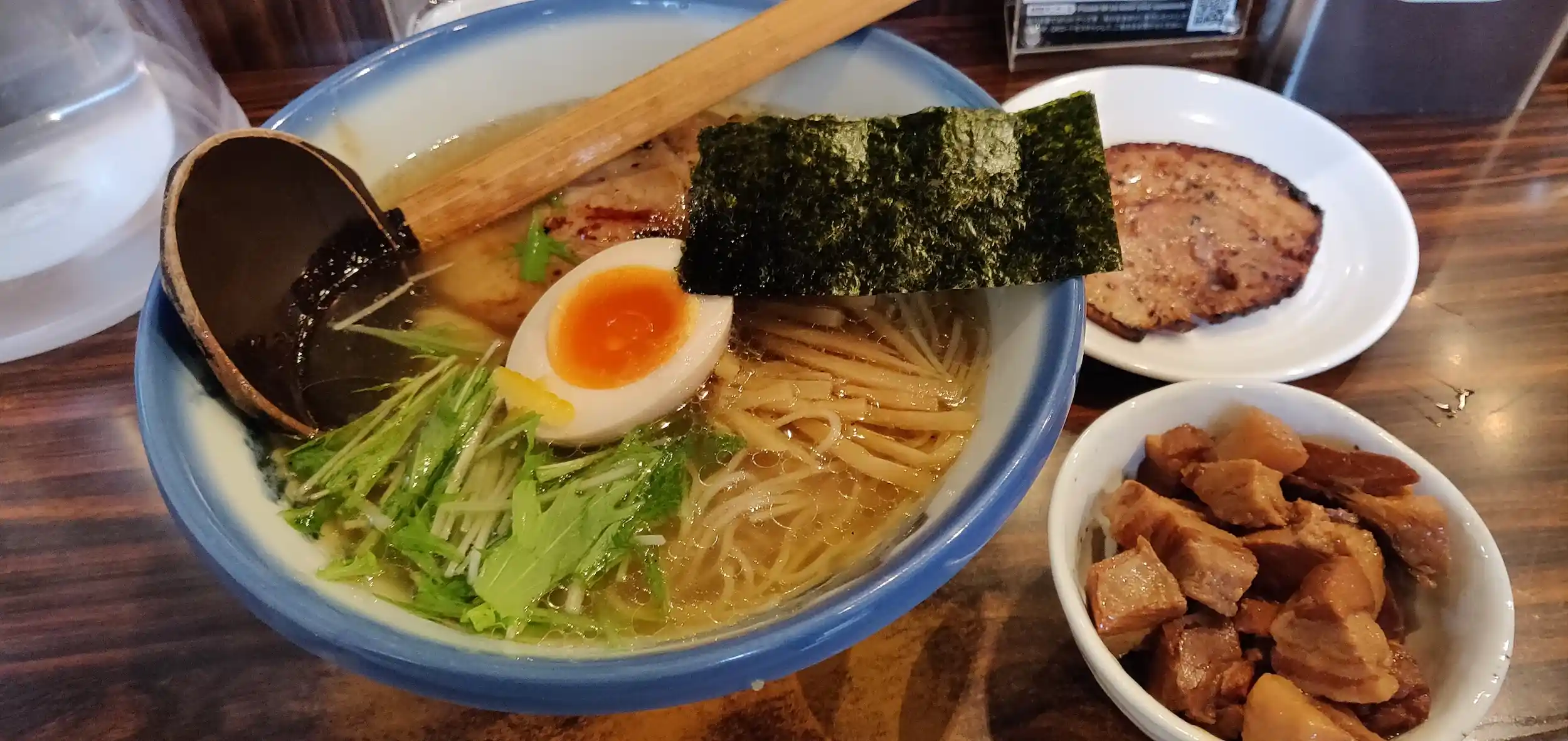

- Chashu (チャーシュー): Thin slices of pork (usually belly or loin) slowly cooked for 3-4 hours at a low temperature (approximately 65-70°C) in a mixture of soy sauce, sake, mirin, sugar, and other seasonings until reaching a tender, melt-in-the-mouth texture. The best chashu maintain a balance between lean and fatty parts, which should be perfectly melted.

- Ajitama (味玉): A soft-boiled egg with a semi-cured yolk, marinated for 4-6 hours in a mixture of soy sauce and mirin. The perfect technique aims for a firm white and a creamy yolk that is solid around the edges but maintains a fluid center.

- Negi (ネギ): Japanese green chives, added both for their aromatic freshness and visual contrast. It can be served finely chopped, sliced diagonally, or julienned, depending on the style.

- Nori (海苔): Toasted seaweed that provides an intense sea flavor. Traditionally, it is partially submerged in the broth, allowing it to soften gradually.

- Menma (メンマ): Fermented bamboo shoots that provide a crunchy texture and a distinctive aroma. They are pre-marinated in a sweet and savory seasoning mix.

Other less common additions include:

- Buttercorn (バターコーン): Sweet corn and butter, especially in Hokkaido.

- Wakame (わかめ): Fresh green seaweed common in coastal areas.

- Benishoga (紅しょうが): Red pickled ginger that adds color and acidity.

- Naruto (なると): White and pink spiralized fish paste, traditional in shoyu ramen.

Aromatic oils also play a crucial role: garlic oil (にんにく油, ninniku abura), chili oil (ラー油, rayu), or chive oil add an extra dimension and help “seal” the heat of the broth.

Ultimately, each ramen-ya creates a unique combination of ingredients and proportions that gives its ramen dishes their identity.

Popular Ramen Variations

The diversity of ramen in Japan is astounding, with each region developing its own distinctive style, adapted to the local climate, available ingredients, and the cultural preferences of its citizens.

On your trip to Japan, we invite you to explore the wide variety of versions of ramen. Due to its popularity, many regional versions of ramen are available throughout Japan, especially in larger cities where you can sample the best from across the country.

Here are some of the ramen considered the best in Japan:

Hokkaido Ramen (北海道ラーメン)

On Japan’s northernmost island, where winters see sub-zero temperatures, ramen has evolved into hearty and comforting variations. Sapporo Miso Ramen (札幌) is the most iconic: a rich miso-based broth, usually accompanied by butter, sweetcorn, and sometimes a portion of sautéed minced meat.

This style has a well-documented origin: it was born in 1955 at the restaurant “Aji no Sanpei” (味の三平), when owner Morito Omori created this recipe inspired by Chinese dishes and adapted it to the cold local climate. The fat from the butter, the calories from the miso, and the carbohydrates from the thick noodles provide the energy needed to cope with the low temperatures.

Travelers to Sapporo should visit the famous “Ramen Yokocho” (ラーメン横丁), an alley with a concentration of small traditional ramen shops, many operating since the 1950s, located in the Susukino district.

Other important Hokkaido variations include:

- Asahikawa Ramen (旭川ラーメン): Characterized by its shoyu broth with a thin layer of oil on the surface that helps retain heat, crucial in this city that records some of the lowest temperatures in Japan.

- Hakodate Ramen (函館ラーメン): A clear chicken and seafood broth with salt, reflecting the fishing tradition of this southern Hokkaido port.

Tokyo Ramen (東京ラーメン)

Shoyu ramen is the emblem of the Japanese capital. Characterized by a clear but flavorful chintan broth based on chicken and dashi (出汁, fish and seaweed broth), seasoned with a specially selected soy sauce. The noodles are usually thin and straight, while the toppings are classic: chashu, naruto, ajitama, and spinach or other blanched vegetables.

Each Tokyo neighborhood has its own ramen tradition:

- Ogikubo: Known for its light chicken broth ramen with shoyu.

- Ikebukuro: Famous for its tonkotsu-gyokai, which combines pork and seafood.

- Nakano: Famous for its old establishments with recipes preserved for generations.

Foodies shouldn’t miss Tokyo Station’s “Tokyo Ramen Street,” a hub of the country’s most famous ramen-ya establishments, such as Rokurinsha (六厘舎), known for its exceptional tsukemen, or the historic Harukiya (春木屋) in Ogikubo, operating since 1949 with its special aged broth.

In recent years, a more refined and lighter “New Tokyo Style” has emerged, exemplified by establishments like Afuri, which uses yuzu (柚子), a prized citrus fruit, to give its broths a freshness.

Hakata Ramen (博多ラーメン)

Originating in Fukuoka, on the island of Kyushu, Hakata ramen is synonymous with tonkotsu (豚骨), or pork bones. Its extremely thick and cloudy broth is the result of boiling pork bones over high heat for many hours. This creates an almost creamy texture that challenges the Western notion of soup.

Its noodles are characteristically very thin and served al dente. A peculiarity of Hakata establishments is the “kaedama” (替え玉), a system by which diners can request an extra portion of noodles to add to the remaining broth. This system arose from the local preference for very firm noodles, which soften quickly, requiring replacement to maintain optimal texture.

A unique feature of Fukuoka is the tradition of “yatai” (屋台), street ramen stalls that set up after dark, creating an authentic and social dining experience. The Nakasu district is home to many of these traditional stalls.

The “Ganso Nagahama Ramen” restaurant is considered the original establishment that created this style of ramen back in 1952, which later evolved into the current Hakata recipe.

Visitors can also enjoy the “Hakata Ramen Stadium” in Canal City, a gastronomic experience space with different regional ramen styles all in one place.

Sapporo Ramen (札幌ラーメン)

Although already mentioned among Hokkaido’s styles, Sapporo ramen deserves special attention.

Sapporo Ramen has a relatively recent and well-documented history. Unlike other styles with unclear origins, we know exactly when and where it was born: in 1955, at the “Aji no Sanpei” (味の三平) restaurant in the Susukino district.

Its creator, Morito Omori (大森盛夫), was experimenting to find a dish that would combat Hokkaido’s harsh winter. Inspired by Chinese cuisine, particularly that of the Manchurian region, and Japanese noodle-making techniques, Omori created a miso-based ramen, revolutionary for the era when shoyu (soy sauce) and shio (salt) styles dominated the scene.

The innovation was no coincidence: miso, a traditional Japanese fermented food rich in protein, provides a rich flavor and greater caloric density, ideal for a climate where the body needs more energy to stay warm. The addition of butter, unusual in traditional Japanese cuisine, reflected Hokkaido’s growing dairy industry, which had begun during the Meiji era as part of modernization efforts.

By the 1960s, miso ramen had become Sapporo’s culinary identity, and in the 1970s, it achieved national recognition when Sapporo establishments began expanding to Tokyo and other major cities.

Its defining characteristic is the use of red miso as the base of the tare, creating a robust and earthy flavor. What makes it unique is the addition of butter, which melts into the hot broth, adding creaminess and richness.

This ramen typically includes sautéed vegetables, such as onion, carrot, and cabbage, in addition to the ubiquitous sweetcorn, grown in abundance on the plains of Hokkaido. The combination of butter and sweetcorn may recall Western influences, but it is perfectly integrated into Japanese tradition.

The epicenter of Sapporo’s ramen culture is the famous “Ramen Yokocho” (ラーメン横丁), a historic alley in the Susukino entertainment district that houses 17 small ramen shops, each with its own interpretation of the classic style. Originally established in 1951 as a post-war black market, it has evolved into an iconic foodie destination.

In these tiny establishments, often seating no more than 10 customers, diners sit at the counter facing the chef, watching the preparation of each bowl. The atmosphere is warm not only from the steaming broth, but also from the proximity between customers and chefs, who exchange comments about the frigid weather outside while enjoying the comforting warmth of the ramen.

Kitakata Ramen (喜多方ラーメン)

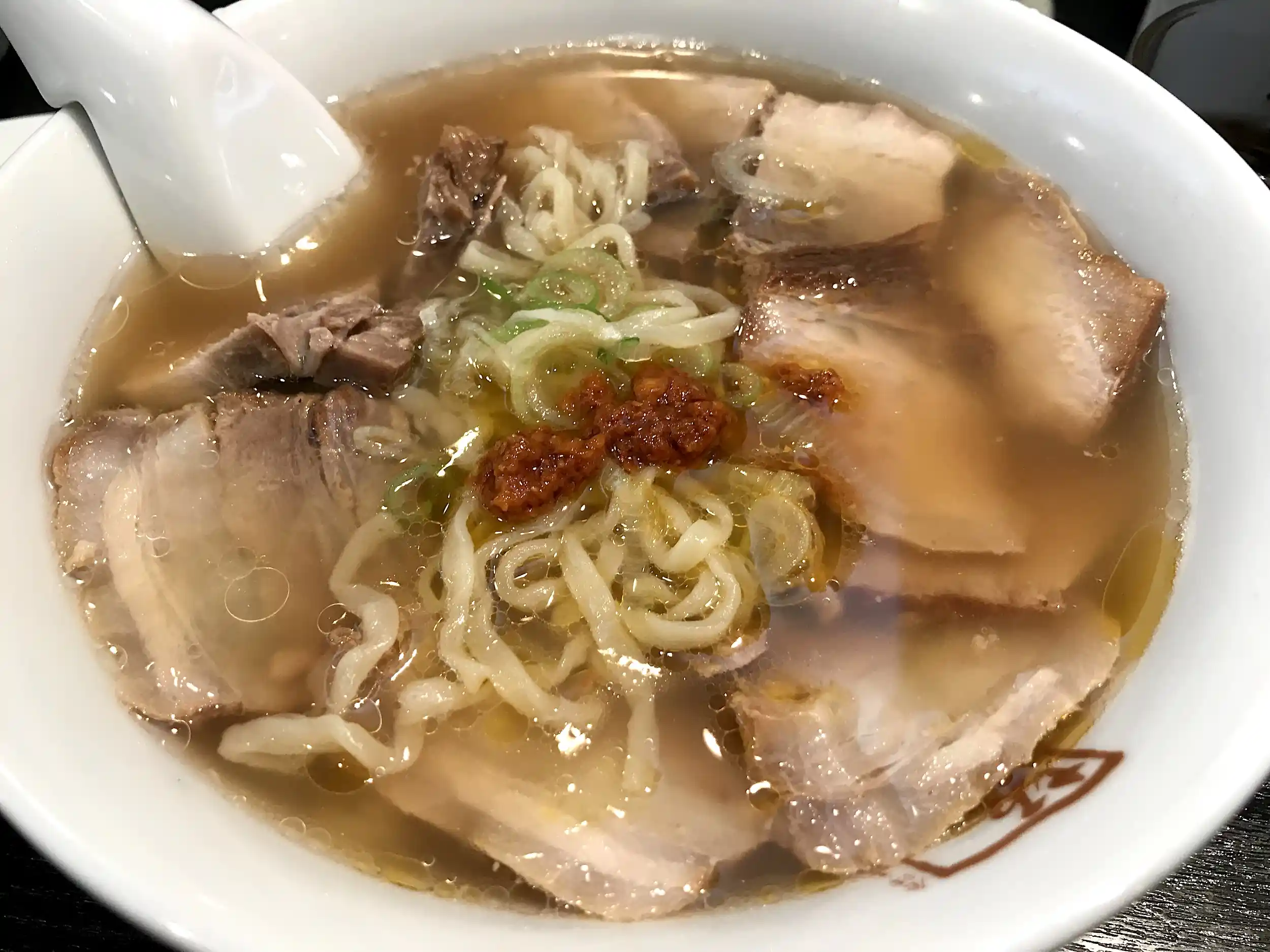

Kitakata Ramen (喜多方ラーメン) represents one of Japan’s “Big Three Ramen,” along with Sapporo Miso Ramen and Hakata Tonkotsu Ramen. Originating in the small city of Kitakata, Fukushima Prefecture, this variety has won hearts and palates for its unique combination of simplicity and depth.

The history of Kitakata Ramen dates back to the early Showa era (1920s-1930s), when traders returning from Manchuria brought Chinese culinary techniques to this mountainous region. Kitakata was traditionally a center for sake and shoyu (soy sauce) production, thanks to its high-quality water and climate conducive to fermentation. These factors proved instrumental in the development of its unique style of ramen.

The first Kitakata Ramen establishment was Genraiken (元来軒), founded by Bannai Shokudo in 1926, which continues to operate today, serving a recipe that has maintained its essence for nearly a century. This pioneering shop established the characteristics that would define this regional style.

What truly sets Kitakata Ramen apart are its noodles. Unlike most styles of Japanese ramen, Kitakata noodles are exceptionally wide and flat, wavy and thick, with a firm yet chewy texture to achieve a specific texture.

These characteristics are partly due to the region’s cool climate: thicker noodles retain heat better and provide greater satisfaction. Traditionally, the noodles were made by hand and left to rest overnight, giving them a particular texture called “hoshi-men” (干し麺, dry noodles) that results in a unique mouthfeel.

Unlike other parts of Japan where ramen is primarily consumed for lunch or dinner, in Kitakata it is traditional to enjoy it as the first meal of the day. Many establishments open their doors as early as 7 a.m. to cater to local workers, mainly farmers and artisans looking for a hearty breakfast.

Other Noteworthy Styles

The ramen scene in Japan is practically endless, with every small town proud of its own version:

- Tantanmen (担々麺) is the Japanese interpretation of dandan mian (担担面), an iconic dish from Sichuan province in China. Tantanmen is considered one of the quintessentially spicy dishes on the Japanese culinary scene. Intense in flavor, it combines powerful aromas and sensations with a blend of spicy chili oil, sesame, and Sichuan peppercorns.

- Onomichi Ramen (尾道ラーメン) from Hiroshima incorporates melted pork fat into the broth, creating a shiny film on the surface. Its flat, straight noodles complement the seafood and shoyu-based broth.

- Wakayama Ramen (和歌山ラーメン), also called chuka soba (中華そば), maintains the old name for ramen, with a strong soy and pork broth, and is served alongside a bowl of rice topped with tonkatsu pork cutlet.

- Tsukemen (つけ麺) is not strictly regional but an alternative style, created in 1961 by Kazuo Yamagishi at his “Taishoken” shop. It consists of cold noodles dipped in a hot concentrated broth. It has gained enormous popularity in recent decades, especially during hot summers.

- Tokushima Ramen (徳島ラーメン) from Shikoku features a distinctive reddish-brown pork and shoyu broth, topped with raw or undercooked egg and minced beef, with options of sweet (甘口, amakuchi) or savory (辛口, karakuchi).

- Kurume Ramen (久留米ラーメン), considered the precursor to Hakata, uses a less processed original tonkotsu broth with a darker color and richer flavor.

- Kagoshima Ramen (鹿児島ラーメン) uses Berkshire Black pork (黒豚, kurobuta) in both its broth and toppings, creating a distinctive and luxurious flavor.

The Sensory Experience of Ramen

Ramen isn’t just a dish to eat; it’s a multisensory experience. Upon entering a traditional ramen-ya, the first thing that hits you is the aroma: a blend of simmering broth, fried garlic, fresh chives, and the deep umami of the broth. The steam rising from the bowls creates an almost mystical atmosphere.

The proper way to enjoy ramen involves a ritual: first, appreciate the aromas, then taste the noodles while they’re cooked to perfection (many chefs estimate they have 5-7 minutes of optimal texture before becoming too soft). The famous slurping gesture (ズルズル, zuruzuru) isn’t rude, but a technique that allows the fiery noodles to cool slightly while infusing them with air.

Japanese diners often start by trying the broth alone, then the noodles, and finally combine both, leaving add-ons like pork or egg for last, true rewards after the main experience.

The atmosphere of a traditional ramen-ya is also part of the experience: small spaces with wooden counters, often with only 8-10 seats, where customers can watch the master prepare each bowl. The constant sound of boiling broth, draining noodles, and the satisfied murmur of customers completes the sensorial immersion.

Ramen as a Cultural Phenomenon

Ramen transcends the gastronomic realm to become a cultural phenomenon. Films like Juzo Itami’s “Tampopo” (1985), considered the first “ramen western,” explored the philosophy behind this dish. The anime and manga “Naruto” popularized Ichiraku Ramen internationally, inspiring young people around the world to discover authentic ramen.

In Japan, “ramen otaku” are fans who travel hundreds of miles just to try a specific establishment. There are specialized magazines like “Ramen Walker” and apps like “Ramendb” where enthusiasts share discoveries and detailed reviews.

The Shin-Yokohama Raumen Museum (新横浜ラーメン博物館), opened in 1994, was the world’s first themed food museum, recreating a Showa-era Japanese neighborhood where visitors can sample different regional styles. Since then, others have sprung up, such as the Tokyo Ramen Kokugikan Mai in Odaiba and the Fukuoka Ramen Stadium.

Ramen is now an internationally known dish, and its popularity is reflected in the increasing number of new restaurants opening around the world. However, Japan still maintains a finesse in its preparation and a concentration of flavors that are difficult to find in ramen dishes in Western restaurants. Your trip to Japan will provide you with many memorable culinary experiences if you immerse yourself in the world of ramen.

Want to travel to Japan? Here are some ideas: